Yesterday, Mike Hulme and I submitted the manuscript of our forthcoming book ‘When Temperature Became Global: A Brief History of the World’s Most Important Index’ to Princeton University Press Now it will go through peer review and subject to any revisions will enter production in time to be published in Spring 2027. This is our brief description of the book:

Numbers shape the world around us in powerful ways and in this short book we tell the history of a hugely consequential number whose story has remained untold. Global temperature is today used to monitor global climate, to signal danger and to organize global climate policy. From the Paris Agreement to the concept of Net Zero, global temperature shapes global politics and our visions for the future. And yet it cannot be experienced by anyone anywhere on the planet and few people know how it is calculated. It is as important as Gross Domestic Product, yet its history remains unknown.

We present the history of this concept in ten concise chapters, explaining what it is, how it has been made, and what it has been used for during the past 150 years. We seek to understand two things. How could an empirical global temperature index for the Earth be constructed that passed the test of scientific credibility, and thus hold political utility? And why have scientists sought to do so, at different times and places?

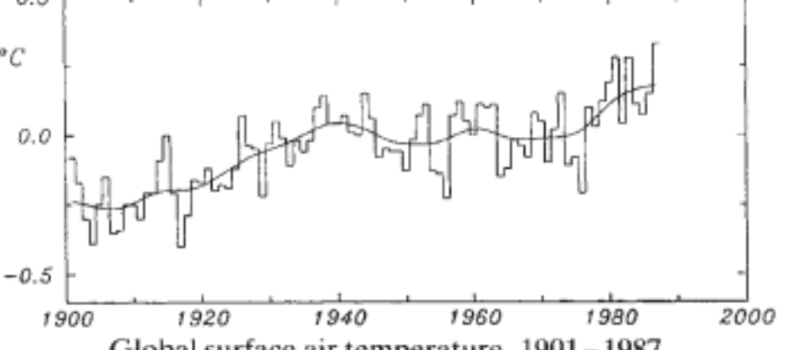

Global temperature has not always had the iconic status it has today. We begin by tracing work by a range of independent researchers who for roughly one hundred years—from the 1870s onwards— developed a variety of large-scale temperature series as tools to test different theories of climate change. Our focus then sharpens in the years around 1980. In this period, scientists increasingly turned to large-scale temperature indices with a new objective: to distinguish possible anthropogenic global warming against a background of natural climatic variability. Researchers working independently at the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia, later in collaboration with the UK Met Office, and at the Goddard Institute for Space Studies at NASA developed new global temperature series which would definitively (if not immediately) transform global temperature from a tool used to study climatic change into what we know it as today: a trackable ‘emperor’ metric that structures global climate policy and discourse, and, by extension much planning for the future.

We conclude the book by reflecting on lessons of this history: that there might have been (and still are) other, perhaps better, ways of measuring the health of world climate, or indeed the well-being of its inhabitants. Global temperature has become central to the way we measure, understand and govern climate change, but as this history reveals, its emergence was not necessary or inevitable. Like any measure, it has advantages and disadvantages. Understanding its history helps us to see more clearly what those relative merits and demerits are. By extension, this history can, we hope, assist considerations of what other measures of the state of world climate might complement global temperature.

January 15, 2026

On December 9, 2025 I spoke with artist Noémie Goudal about her immersive installation ‘The Story of Fixity,’ an installation in a viaduct in Borough Market exploring the role of water in shaping landscapes. Chaired by Artangel director Mariam Zulfiqar, who commissioned the piece, Noémie and I discussed the history of efforts to understand water and her intricate process for creating dynamic projected images which explore flowing colors and form evocative imaginary places.

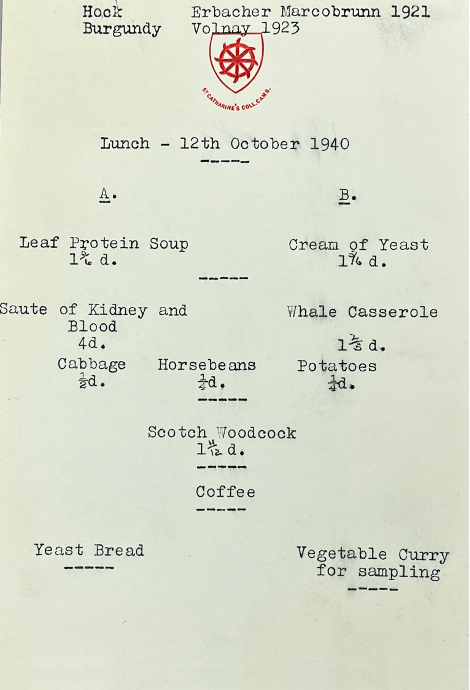

In July 2025, I participated in The Oxford Food Symposium, where I gave a paper on the history of an obsolete emergency, the world protein gap. The theme of this year’s event is Food and the Elements. My paper considers how the history of a panic over global protein supplies, and the resulting efforts to discover or create new sources of protein, including from leaves and by feeding microbes on the byproducts of oil refining, has important lessons for today.

The menu below is for a lunch served to Lord Woolton, the Minister for Food, at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, demonstrating a range of foods on which the country could subsist in the event of total blockade. It included Leaf Protein Soup. Woolton was not impressed. He recorded in his diary that he had to resort to a Turkish bath and massage to rid his liver of the protein he’d consumed as part of the ‘purely scientific lunch.’ (from Norman Pirie papers, RS, NWP c.149, at Bodleian Library, Oxford).

In June 2025, a second edition of my biography of Marie Curie was published by Haus Publishing, 22 years after the first! It has a new introduction in which I consider Curie’s intense antipathy to attention and why we should still be interested in her, though she is a terrible role model in many respects.

In May 2025 I signed a contract with Princeton University Press to publish The Woman Who Took on the World: Dana Meadows, the Limits to Growth, and the Invention of Systems Thinking (world rights). I am extremely pleased to be working with the Press, and in particular with Eric Crahan, who edits their history of science list in addition to serving as Editorial Director for humanities and social sciences. With thanks to Peter Tallack, of Curious Minds, for getting this over the line.

On April 14, 2025, I participated in a symposium to celebrate the life and scholarship of my friend Catherine Will. It was moving and inspiring to hear from all those with whom Catherine worked.

In November 2024, I attended the History of Science Society meeting in Mérida, Mexico, the centenary of the society. I gave a paper titled ‘Time is a Resource: How Should We Spend It? On History, Climate and Activism,’ in which I considered how scientists and historians have used different temporal concepts, including deep time, crisis, emergency and dynamics.

While I was there, I rode the new Tren Maya between Cancun and Mérida, a fascinating and enjoyable experience.

On April 11 2024, I participated in a terrific workshop on ‘Disciplinary Crossroads: Between History of Science and Environmental History,‘ organized by Carolina Granado (PhD(c) iHC-UAB), Hèctor Isern (PhD(c) iHC-UAB), Max Bautista (PhD(c) UCLouvain). My paper was an opportunity to this about climate science, history and activism, with a focus on some interesting papers published on systems history of technology in Technology and Culture by Pete Drucker (below) and others.

In June 2023 I spoke on “How interdisciplinarity saved the world: global problems and climate change at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, 1972-1988” at a conference on Practice and Place in History of science and knowledge hosted by the Finnish Literature Society and the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters.

West Churchman was a philosopher who helped found the discipline of management science and wrote influential books on systems thinking. He wanted to better understand the relationship between systems and ethical human relationships so that systems thinking might have a chance of bringing about positive and lasting change into the world.

In this short film I made about Churchman, he asks a few disarmingly simple questions about the ‘good’ of systems. Churchman was often to be found knitting during academic seminars. With thanks to Kristo Ivanov, who generously gave me permission to use footage from his 1987 interview with Churchman.

An event was held in China on March 31, 2022 to mark the 295th anniversary of Newton’s death. Three books on Newton recently published in Chinese were highlighted, including my The Newton Papers, recently translated into Chinese.

More than 43,000 people attended the online event.

On March 12, 2022, I spoke at a conference on “The History of Climate Science Ideas and their Applications,” organised by the history section of the Royal Meteorological Society.

On December 1, 2021, I spoke about what historians can offer to public discussions of climate change with Mogens Laerke of the Maison Française Oxford in his “Science and the Public Sphere Seminar.”

On Friday, September 24, 2021, I participated in an online discussion of the three heavy-hitters held in the collections of Cambridge University Library–Newton, Darwin, Hawking.

On October 2, 2021, I spoke with Aminul Hoque on a panel on “Science museums and the ‘culture war’ ” chaired by Sara Abdulla and sponsored by the Association of British Science Writers.

In February 2020, I gave a talk on “Waters of the World: The Story of Climate in Six Lives” at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ.

In April 2019, I spoke about the Newton manuscripts held by Cambridge University Library.